FAGIOLATA part one // Camburzano // Piemonte // ITALY

Original community street food, this wet bean stew cooked in the copper pots used to make cheese is an example of mountain food alchemy. Looks like gruel, tastes of heaven. And pig.

Can you believe it, but I actually accidentally erased the photos I took of this incredible event I witnessed. I think it’s all good though, as what I learned about this excellent dish is far much more than what I can fit here, and I will return next year.

But in the main, it is a wonderful celebration of abundance and scarcity, community, and the joyously wilful absence of health and safety protocols.

This got me to thinking how this dish is so contextually monumental, I am going to release it in two parts. This, the first, is a description-heavy (in absence of my lost photography) introduction as to why it might be one of the most important dishes here at Up There The Last and part two, which I shall publish this time next year, will go into depth as I join the villagers of Camburzano at 5am to begin cooking and discover the intricacies of the recipe, uncovering the fascinating traditions of Carnevale and address the “killing of the pig”.

In the meantime please enjoy this long read, and the photos I took from l’an-cà da fé by Burat and Lozia, and Lettere da Gustare by living legend Mina Novello. Two of my favourite books, written by heroes.

Paid subscribers will find a description of an old recipe I found for fagiolata.

FAGIOLATA

Part One

Max Jones

With the passing of years I realise that one of the real tricks to enjoying life is to celebrate and harness contrast. It is within your power to amplify the meaning of your day-to-day.

At home, we spend the evenings close to the open fires used to heat the house, the encroaching chill from the rest of the cottage makes us dart to the kitchen for hot tea on tip-toes, the visible steam rising from the cup tells us not just of how cold the room is, but rather how hot the tea is, as we run back to the warmth of the glowing yellow fire that stimulates our senses in the now absolute cosiest part of the cold house. And I like to sleep with the window open. At this time of year I jump into my freezing bed wearing a poppy-red thermal onesie as I curl up and wait to warm up the stiff, cold sheets and when I am under, the winter breeze I feel across my forehead shows me just how toasty I am.

Being able to perceive these moments of contrast enriches our lives and I get excited when I come across long-established examples that exist in deep culture. Which brings me to one of my favourite dishes, fagiolata, that I came across first on a brisk February walk through the Village of Camburzano in Piedmont.

Fazolá (fa-zoo-LA) is the Biellese dialect for fagiolata, a hyper-local community dish that comes from the word fagiolo, meaning “bean”. It is a rich stew with an even richer history, cooked for about five hours on a fire with vegetables, beans, pig skin and salame.

On wintry walks in Camburzano you don’t meet many people, mostly just dogs that run up to a fence to bark at face level, hurrying you along. It is unusual to be outside and you notice the mountains, brown and grey in the distance. Through the gloom the houses seem lifeless, their windows shuttered shut. This is the way of the mountain folk, a reserved people that keep winter out, warmth in and themselves to themselves as they save on firewood and wait for spring to spring. My Aunt would always use this winter-time metaphor to describe the personality of the Biellese, who can often be perceived as unfriendly and reserved (herself included, to justify her ill-temper).

One cold and damp day on my usual route, I perceived the bonfire smell of woodsmoke. There was a very homely feeling to it too, as I recognized familiar stew-like aromas of soffritto, meat stock and fermented pig, that hung in the air. These kitchen smells I associate with being indoors became even more enticing in the cold outside. They seemed to bring the village energy, almost colouring the village into life. My senses tingled as I looked around to find the fire whilst I paced the streets, eventually seeing blue smoke rise around the pink church bell-tower that led me to the village centre below our home.

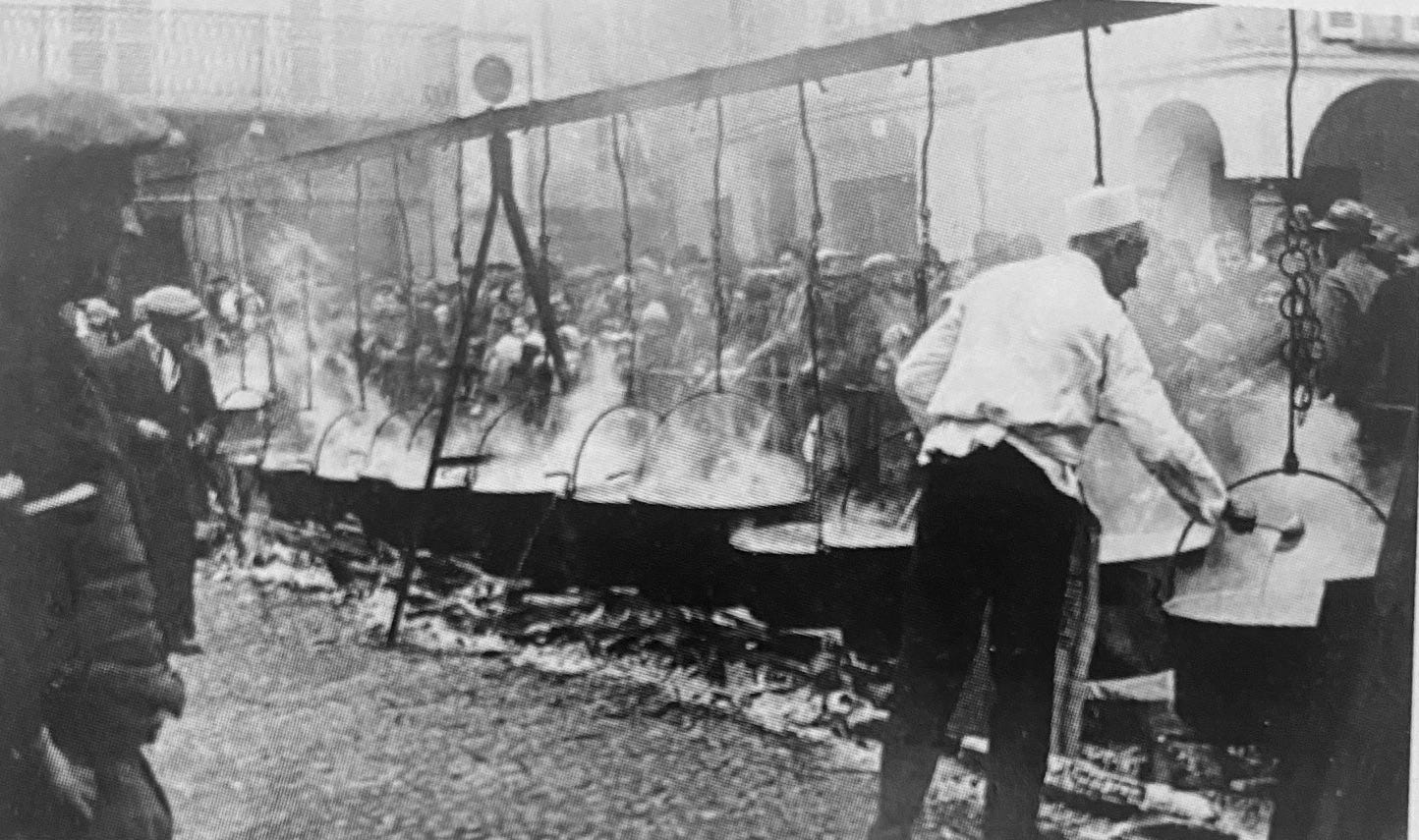

Sure enough, clustered by the church was a hive of activity and colour. Green gingham-clothed trestle tables with magnums of label-less nebbiolo and bread by a row of ten vast copper vats, each the size of a small washing machine, raised on a rusty frame of crudely welded scaffolding poles above fires fed with acacia logs, fruit boxes, bits of plank and the rest.

I did not know it at the time, but I was about to stumble upon one of the best examples of what I love most. A living tradition created to feed a community based on geographical and bio-cultural rituals, that just makes so much sense. Pure in its practical application, it is an expression of confidence and identity from which we can all learn.

-

The last time I saw one of the giant copper pots they were cooking with (a ubiquitous piece of mountain kit) was in the back of a pick-up truck when we came off the mountain from cheesemaking for the desalpa transhumance last October.

Flames licked their matt-blackened sooty exterior, bubbling a kind of copper-coloured gloop inside the glossy copper interior, just beautiful to behold. Each one was stirred continuously by a man with a large wooden paddle, almost like an oar, used for polenta and most probably made of chestnut wood from the forests above the village.

Some of the stirrers I recognised to be herders and country-folk from the village and elsewhere in the Elvo valley with their brightly coloured plaid shirt workwear and enormous hands. Others were of the penne nere, black-bearded men with proud crow feathers poking out of their beaked hats, denoting their Alpino identity. These are a very tight faction of the Italian military who specialise in mountain terrain and who, on completion of service, remain loyal to the mountain communities they are from.

Because of the large posters plastered with a broom to surfaces around the town a few weeks prior, or even just the delicious stew-smoke working its way through the streets since 5am when they began to cook, by lunchtime a crowd had formed. And in middle of it all, against the grey and silent backdrop of winter’s dead mountain in this dormant village, the parish priest in pea-green and gold vestements blessed the crowd, flinging holy water amidst the smoke and flames and feathers and steam and into the gurgling cauldrons of fagiolata.

I absolutely love it. Holy Water on the ingredients list!

When it was ready a friendly, chattering queue formed, with stories told and news shared among the townsfolk, with more cars arriving from the centre of the Biella a couple of miles away (each commune has a reputation for the quality of their fasolá and Camburzano is one of the greats). The city-folk wore new puffer jackets bought in the January sales, and the locals a varied collection of faded ski-jackets from the 80s and 90s. The older women wore ancient furs from when Biella’s wool industry was booming.

Everyone carried large pots and pans (usually a pressure cooker) with which to take home their fagiolata. The hefty cooks worked hard to feed everybody, interacting with the crowd with cheers and wine in plastic cups, slopping into the miss-matched kitchenalia hundreds of portions with enormous ladles and a few cooked salami, which were all taken home and eaten on this gloriously lively day.

Fagiolata is not bought or sold, as I discovered after running home to collect my pressure cooker and returning to join the queue. I couldn’t quite understand how the system worked, and when it came to my turn arriving at the small table run by an elderly woman behind a metal change box, I handed her €50. I had thought to myself that since there were five of us that would be eating this ephemeral meal back at home, a tenner per plateful seemed pretty darned good to me.

“How many portions do you need?”

“Five please”

“Well thank you! That’s fantastic!”

With that she slammed her box shut, grabbed my cooker and flung it to the friendly chaos around the fires and pots, the cooks now in their vests, sweating and drinking wine, working well.

“Five portions for the generous man! And make them big!”

I shuffled down the gingham service line whilst my cooker was filled, to another man who was waiting for me with two heaving handfuls of boiled salame, which he stuffed into the top of my pot of fagiolata with a wink. I looked back down the line at the woman at the donations desk, who gave me a nod. I closed the lid tightly with its large handle, understanding why the pressure cooker was the container of choice amongst the Camburzanesi. I wrapped it in a tea towel so as not to stain myself with the ladler’s errant slops on its exterior, holding it beneath my coat to stay warm. It was a joy to feel its heat and we kept each other toasty against the cold winter wind as I headed home at speed.

-

Fagiolata doesn’t look like much, yet the flavour of this copper-coloured, lumpy paste is absolutely enormous. Again, in no small part due its contrasts. Like the familiar and homely smell that brings the cosiness of a kitchen to its context outdoors, once inside and around the table, the pot emits an aroma of wood-smoke that rises off the stew itself, now bringing a smell we recognise from outside, indoors.

Through constant stirring, it is exposed to the smoke of the fire that cooks it for 5 or 6 hours. As it envelopes the pan, smoke sticks to the fat and oil of the stew that gives it tremendous BBQ depth. The beans are broken down from lengthy cooking with tomato, celery, onions, and stock made from boiled meat, salame, and bones, with plenty of pig skin, whose fat gives the fagiolata a pleasing sheen and whose collagen imparts a savoury, tacky quality that feels unbelievably nutritious and warms you up like nothing else. I don’t think a single plate of food has ever filled me as fagiolata.

It has all the hallmarks of the deliciously resourceful, nourishing and waste-less cuisine that I have come to love so much from the people of these mountains, and after witnessing it myself, I wanted to know more. I uncovered some interesting ideas and promising leads, which I shall mention now, with the keen desire to return to part two of this piece next year where I will finally take part in the cooking, and learn of the stories first hand.

I spoke with local elder Mina Novello and read a story in her book that for her, the variety in colour and shape of beans were always a thrill to observe. Most gardens would have had a smattering of fagioli growing as a staple food and when she was a child, opening the pods of patterned beans inspired the same gleeful anticipation as Kinder Eggs did for my generation. At home they formed a staple at this time of year, as preservation by desiccation in late summer meant stable food to survive the winter. The most common way to eat them was simply boiled and dressed like a salad with finely sliced raw onion, oil (olive or walnut), pepper and a dash of vinegar.

More rarely, they were gently stewed with garlic, onion, bay and a tomato, sometimes with a piece of salame, cooked in the traditional clay Bielline pots made from the red earth of Ronco left on the far corner of the wood stove to gently plop and bubble away throughout the day. I adore this fluid way of cooking over the heat source that warms the house.

When I look at fagiolata, and when I taste it, I know I am eating something that has not really changed that connects us to the ancient past. Specifically what attracts me is its honesty, how it stems from a time before the abstract rules of food-safety authorities, when people cooked over fire in the middle of the street and ate together as part of a community of people who trusted each other.

It is wonderful how it happens only once a year and because of this precious scarcity, it is much easier to imagine past generations in this exact place around the village church cooking in the same, hundred-year-old copper pots used to transform the mountain above them into cheese, and also used to cook this dish that would have tasted exactly like it does right now. It is an event that has not been commodified or homogenised, and goes a long way to celebrate the identity of the place and its people.

From my research into polenta (I would need 50 substacks for this), I came to learn that a lot changed during the Age of Discovery. As we can see from the peasant subject of "The Beaneater” by Carracci (1584), the hero legume that kept millions alive and kept famine at bay for millennia was the black-eyed bean. Most of the dishes as we know them today use varietals brought from the New World during this period, which were more easily adapted to the cucina-povera recipe canon because of the pre-established black-eyed bean that paved their way, and was less “difficult and traumatic” as Novello says, than the introduction of the tomato or potato. The beans might have been different, but the method for cooking with beans remained the same and is continued in fagiolata today, directly connecting us to the ancieant past.

The fagiolata event itself became formalised in the 1800s when the festival of Carnivale rose to a peak of abundant eating and party-time, before the fasting period of lent. It was often a time to use up all leftover meat (ltn. carne = meat, levare = get rid of), a little like spring cleaning the larder before going into a period of fasting, when ingredients would be collected from all the townsfolk by the young men about to go on military service. Those who had something to give, gave, and those who didn’t were still welcome to eat the communal fagiolata. It saw a peak in activity between the wars, bringing communities together in periods of loss to rebuild, offering stability through ritual and reinforcing identity, rising again in the ebullient 1980s.

The fagiolata coincides with another ritual, the killing of the pig which would have taken place usually between November and February when food was running low and the mountain pasture inaccessible for its snow. It’s an ancient practice we can date to the early middle-ages as November was called “Blōtmōnaþ”, or the “blood month” when animals went for slaughter.

This meat was turned into all sorts of preserved foods, like pancetta, lardo, salsiccie and salami for the year ahead, where everything was used, even bones were salted and stored in wooden boxes for use in broth. Pig slaughterers were in high demand as a skilled trade, something I have come across first-hand when I met one’s widow in the retirement home of Camburzano earlier this year. Those whose pantries were freshly stocked with pork would share their abundance which is why salame forms such a central part of the dish. The broth which forms the stew’s base contains off-cuts like the head, skin and trotters of the pig that were often given along with salame to the fagiolata cause.

The name of the dish comes from the event itself. Fagiolata translates to something like “bean fest", or “bean off”, or “the big bean get-together”. Something related to beans, that is large. Be it the pot they are cooked in, or the gathering around the event itself. It is a community event made by the people, for the people. Proceeds of the event still go towards whatever cause the townsfolk decide, like fixing roads, acquiring hospital equipment or in the case of Camburzano, supporting the local nursery. And everyone is fed.

Watching all this, being caught in the middle, observing and engaging, I am reminded of my aunt’s description of the Biellesi. How perhaps their highly valued privacy and apparent reticence to being openly social exists because of the incredible contrast presented by this joyous explosion of life, that punctuates the winter with community and togetherness. Maybe it is because of the spirit of Carnevale that people feel they can gather this way, giving an excuse to behave extrovertedly. Some would say that the spirit of Carnevale is to nod to “less civil” times, and forgive this one-off behaviour, but I did not experience it this way. It felt weighty with the clout of heritage and pride, and the joyful energy that comes from eating together outside. Everyone responds so well to this, and actively sees their time, effort, love and money going straight back into the community.

And with all the little contrasts that make up fagiolata, balance is found. It’s the way I like to live. I can’t help but think how it might be the crowning recipe at the very core of my work. I chuckle at the thought of the herders and country-folk condescending to fill HACCP plans on an ipad, or the man lifting salami onto colour-specific plastic chopping boards wearing plastic gloves. How glad I am for the feathered felt hats of the Alpini instead of blue hairnets, and how the woman’s change-box rings with coin flowing from hand to hand in a felt gesture of giving, instead of the soulless bleep from a sumup machine. For me, the rich heritage of this hearty event throws into question the rules and systems that we willingly submit to on a daily basis nowadays, and with each discovery I make of the things close to my heart, I find the laws behind food production increasingly patronising and irrelevant.

Fagiolata is a chance to stay thunderingly connected to an honest and sensible way that once was where everyone, everyone taps into the same joyful congruence of giving, eating and being, with the promising return and cycle of the seasons.

Here’s an awesome old recipe for 100 portions of fagiolata. I’ll be working on how to make a good one at home this year!

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Up There The Last to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.